Reflections on character (part 1): arrival at Birkenau

This first in what I hope will be a series of reflections on character is on spontaneous compassion as exhibited by the Fried girls of Kisvárda.

My parents’ experiences and reactions to experiences during the Holocaust helped them teach me important lessons about noble characteristics in man as well as lessons about the darkest side of humanity. In our time, these lessons are not merely testimony to what people have endured in the past, they are beacons for what we must fight to preserve as characteristics in ourselves and, by extension, in our collective character. It is too easy to be consumed by what we must fight against. However, to sustain one’s willpower to fight against an adversary, one must also know what one is fighting for and this must be something one believes to be just and noble. We must reconnect with our common humanity or else risk being depleted or, worse, becoming consumed by destructive impulses, much like the adversaries we now have to fight so that we may preserve what we love.

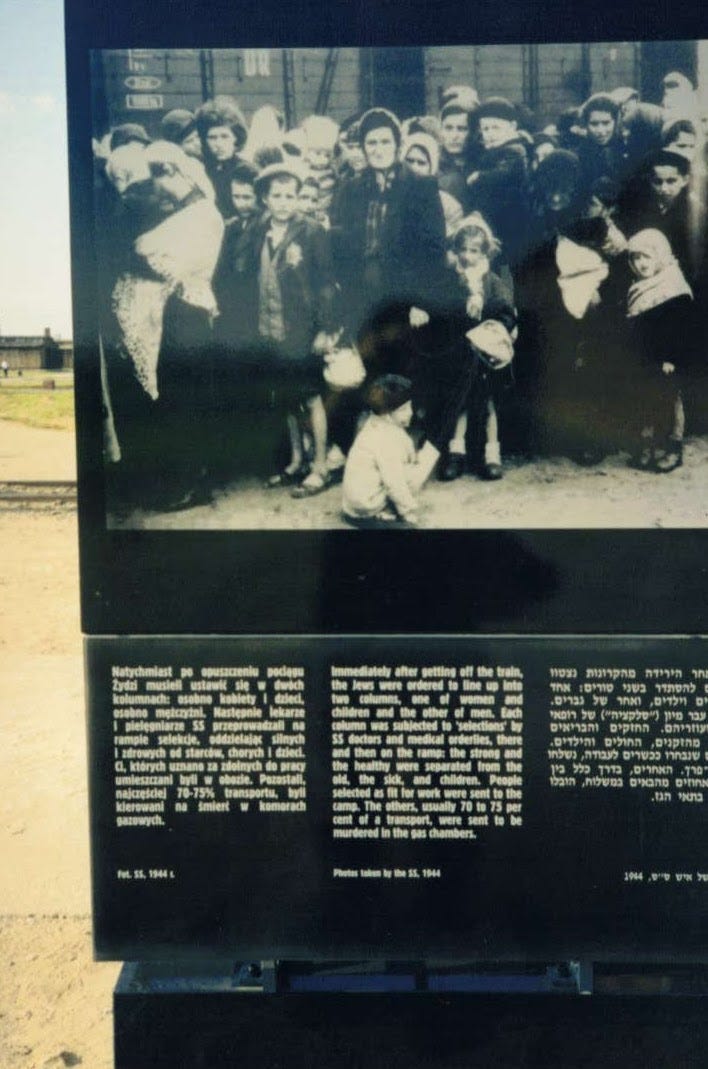

Let me start in this first post on these brief reflections with my mother.1 In the spring of 1944, at the age of 16, she was forcibly sent from the Kisvárda ghetto in Hungary to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp along with her two sisters (one younger and the other older), her parents, her beloved grandmother, and other family members. When the packed train arrived at Birkenau and the Jews were unloaded, she was separated from her family. She survived, yet the rest were gassed and cremated. She did not know their fate right away, but in her grief of being separated, she threw herself down on the ground and refused to go on. Luckily, two girls who had lived nearby her pulled her up and forced her to keep moving along in the line that was forming, imploring her not to let the Nazis shoot her.

Had those girls not been there at that moment, it would probably haven’t been long until she was shot, beaten, or sent to the gas chamber. The Fried girls saved her life.2 They did not have to do so. Even stopping momentarily to help my mother put them at great risk, but they did it anyway. They showed humanity towards her and if they hadn’t, I would not be writing this and my two children would not exist. A lot would be different.

Actions matter. This is one of the first things I learned from my mother’s experiences. Actions that mattered in the past matter today and they will matter tomorrow. Our most important actions will not only matter when they are taken but will continue to matter through time because many other meaningful events will be contingent on them. In other words, their causal effects percolate through time, fanning out rather than being squelched.

It is important to remember that our actions matter. If they are remembered, they can go on having meaning. Once forgotten, though, they are lost forever. Think for a moment about how many causes of events throughout history can no longer be recovered because they were at some point either forgotten or unknown by all.

Did the Fried girls’ kindness to my mother in her moment of despair, when she was willing to sacrifice life itself, follow a decision? Did they perform even a rough utility calculation of the kind economists, decision theorists, and utilitarians are fond of at least recommending to others: the risk to us is this, but if we save Vera it will be worth that? I don’t think so. I doubt very much that there was any debating the reasons for or against saving my mother.

The Fried girls did the right thing in that moment because they were compelled by their humanity even as they suffered their immense grief and fear. And grief it was, for, according to my mother’s report, they had just been separated from their pregnant mother moments earlier.

Immanuel Kant was correct when he (in German) said, “Out of timber so crooked as that from which man is made nothing entirely straight can be built.”3 However, some things made of such timber are far straighter than others, and the Fried girls were just such examples.

Earlier I said that the Fried girls did not have to save my mother, but here we encounter what seems at first to be a contradiction. If they acted without deliberation, then in what sense is it true that they did not have to save her? Perhaps they did have to save her because of the straightness of their moral timber and the corresponding automaticity of their moral reflexes.

Then why does the statement “they didn’t have to save her” still resonate? Perhaps it is because even when we speak about a particular individual or pair of individuals, as in the present case, we recruit information about counterfactual alternatives to these individuals. We can imagine a distribution of different people’s responses and it is easy to imagine that many, if not most, would not have put themselves at such great risk.4 Thus, we can, at the same time, maintain that they did what they had to do and that they did what they didn’t have to do.

I hope you see that the contradiction is merely apparent. No harm to the law of the excluded middle has been done. Both perspectives speak to the Fried girls’ character. When we say that they did what they had to do, we are taking the “inside view” (as Daniel Kahneman put it) and reflecting on the goodness of their character and their moral reflexes. When we say they didn’t have to do what they did for my mother, we take the “outside view”—the distributional view—and contrast them with real or imagined others who would not be cut from timber quite so straight. To use Isaiah Berlin’s Kantian turn of phrase, we can imagine the Fried girls against a veritable sea of bent twigs.5

The Fried girls performed a simple but genuine act of kindness on what was surely one of the worst days of their lives. My mother never wrote more about them in her memoir, but we know that pregnant women in Auschwitz were likely to be sent to the gas chamber. Their mother was very likely murdered the same day they saved mine. I also don’t know what became of the two girls, but the earlier footnote I provided indicates that they might have been murdered in June 1944, roughly two to three months after their arrival. I wish I had asked my mother this question when I had the chance, though she might not have known the answer.

Had my mother not recorded the Fried girls’ act of compassion in her memoir in no more than a couple of lines, knowledge of their effects would have been lost. Only my mother could have recorded this, and remarkably, she did. Such examples should not only give us hope but serve as a compass.

Here I draw mainly from material described in my mother’s memoir, A Survivor’s Memoir by Veronika Schwartz [ISBN 0-88947-369-2, Volume 15h], which can be found here.

In my mother’s memoir, she spelled their name as Freed. However, it was more likely to be Fried. A search of the Yad Vashem database reveals multiple instances of girls or young women with the surname Fried murdered at Auschwitz, but no record of Freed. However, I could not locate records that identified the matching street name. However, I located records of two Fried sisters who were murdered at Auschwitz in June 1944 and they lived on the street that intersected my mother’s street and which was within walking distance. These girls would have been 11 and 16 at the time and the two relevant records are here and here, so perhaps they are the two sisters my mother wrote about but I cannot be sure.

Immanuel Kant, ‘Idee zu einer allgemeinen Geschichte in weltbürgerlicher Absicht’ (1784), Kant’s gesammelte Schriften, vol. 8 (Berlin, 1912), p. 23.

If you doubt this, read, for example, Elie Wiesel’s Night, especially the ending where he quotes the head of the block in Buchenwald: “Listen to me, boy. Don’t forget that you’re in a concentration camp. Here, every man has to fight for himself and not think of anyone else. Even of his father. Here, there are no fathers, no brothers, no friends. Everyone lives and dies for himself alone.” (1960, p. 105). And Wiesel writes, “I listened to him without interrupting. He was right, I thought in the most secret region of my heart, but I dared not admit it.”

Isaiah Berlin, The Bent Twig: On the Rise of Nationalism. In I. Berlin, The Crooked Timber of Humanity (1991). Fontana Press.

I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau twice in the 1990s. On one occasion, I was accompanied by a colleague whose mother and father had survived internment there. The experience was emotionally overwhelming for him, myself and the others in our small group. I will and cannot ever forget having been there and taken in what it all meant. I thought at the time that everyone on Earth should visit and understand what really happened. Anyhow, thank you very much for your story. Human dignity and compassion. Indeed...