Reflections on character (part 2): on creative risk-taking and facing the music like a man

In 1943, as a slave labourer my father found a creative way of saving energy while undermining the Nazis, but when the plan was discovered, he gave himself up to protect others.

This is a short but true story about a real man named Miklós (Miki, Nick) Mandel, my father. He was born in Budapest in 1921, and by 1938 at what today would be the unripe young age of 17, he was the manager of quality control at Tungsram.

His rapid rise in the company was the result of his poor performance as a factory worker. He was very slow at piece work so he applied for a quality control position which he excelled at. Thus, in a short while, he went from lagging behind other workers on the factory floor to managing the quality of their output. I asked him, “But how did you know what to do there? How on earth did you figure out how to improve the production of lightbulbs at 17? Did they teach you that in technical school?”

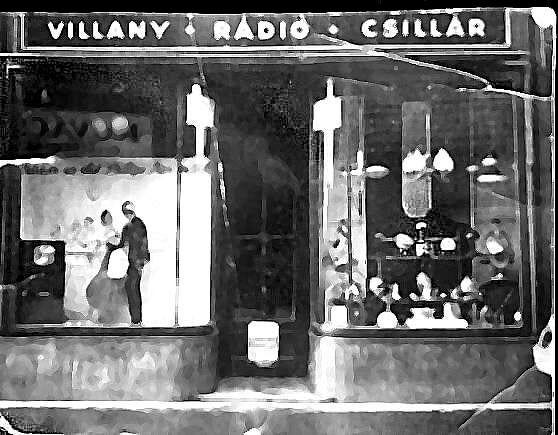

The truth is he was an experimentalist from childhood. He had no toys growing up but played with electronic parts making home-made radios and other devices. His father was a skilled chandelier maker and his parents had a store that sold electronics. So when he got the job, it was just a scaled-up version of childhood play for him, and the toyshop was much more extensive. He could build a micrometer out of spare parts and so he did.

However, by 1943, a mere 5 years later, he was a slave labourer in Buda, Hungary. For a while, he worked on a technical project where he made field antennas. Recalling that assignment during one of my interviews with him about his wartime experiences, he laughed, noting that he later realized he had made a serious mistake in how the parts were connected and that they would all have broken down when soldiers tried to use them. (As any good experimentalist knows, things don’t always go as planned). Fortunately, he didn’t get punished for this since the antennas were sent away to different locations.

But when the Nazis arrived in Hungary, he was transferred to a manual labour job where he had to cut wood and stack it in cords. This, as he noted, was an exhausting job and the prisoners were poorly fed.

He realized, however, that there were many dead tree stumps in the forest. These took up considerable volume but were light and easy to move, like styrofoam. So he creatively placed the deadwood stumps in the middle of the cord and then placed hardwood logs on the outside like a casing. From all appearances, the cords looked proper. It worked splendidly for a while and other Jewish slave labourers caught on and did the same thing. That is, until one day some knucklehead leaned on a cord that had been constructed using my father’s method and the whole thing collapsed.

The guards noticed and demanded to know who was responsible. They said that if no one came forward, they would punish the whole lot of slave labourers, depriving them of food and keeping them outside without shelter. Without hesitation, and yet knowing there would be dire consequences, my father raised his hand and said it was his doing.

He was right about the dire consequences. The guards bound his hands and feet to a pole and hung him upside down for hours until he was numb and in agony. Then they cut him down, letting him fall to the ground. I guess he was lucky because they could have shot him instead.

My father was a slave labourer simply because he was Jewish. He had many horrible jobs but when he told of his account he somehow found a comedic way of highlighting the absurdity of these situations. He would describe his punishment and then without missing a beat, just go on to talk about the next job he had. Not once in my life, did I even hear him whine about anything. There was no melodrama.

When forced to work for the enemy he availed himself of opportunities to mess them up and increase his chances of survival by saving his energy, but he would not let other prisoners take the rap for his actions, even when he was fighting just to stay alive.

He was a creative risk-taker in dangerous times but, when necessary—including when morally necessary—he faced the music like a man and carried on.

Thank you David for both this and the previous part about the Holocaust experiences of Mom and Dad. Dad was not one to dwell in the past. We're fortunate that you were able to convince Mom to write her memoir and for Dad to record an oral history with you, otherwise so much about our parents and their family life would have remained unknown. Dad's imperfect command of the King's English made his playing Scrabble with us hilarious. After the din of the Fleetwood factory on Paré Street, he sought peace and quiet sitting in a small boat on the lake in the Laurentians, fishing for small mouth bass. His life serves as a model of resilience after trauma, of perseverance, modesty, humor, and and genuine lifelong love of Mom and his family.

Stories like this must be preserved! Thank you for sharing.